Terracotta temples in Bengal may ring a brass bell for some. But terracotta mosques? Rarely. Even

Similar examples of Islamic architecture can also be seen in Bangladesh, which was once part of the Bengal Suba, a mediaeval administrative unit.

At the end of the 12th century, Ikhtiyar al-Din Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khilji attacked the Suba following his successful conquest of Bihar. At that time, although the primary local material of construction was clay turned into bricks, stone was also imported to make certain sections of the temples and, crucially, the idols. Brickwork was used for building major portions of the temple, but lesser terracotta decorations were in existence back then as well. In the chapter ‘Sultanate Mosques in Bengal Architecture’ in Muqarnas 6: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture, Professor Perween Hasan from the University of Dhaka suggests that the pre-Muslim period temples in the region were ‘in stone or brick in the Orissan nagara or rekha style that has little place for plaque ornamentation, though it does use ornamental brickwork’. She also draws attention to the fact that stone sculptors, who had the honour of making the deities, ‘enjoyed a status higher than that of the terracotta maker whose work belonged to the folk tradition’.

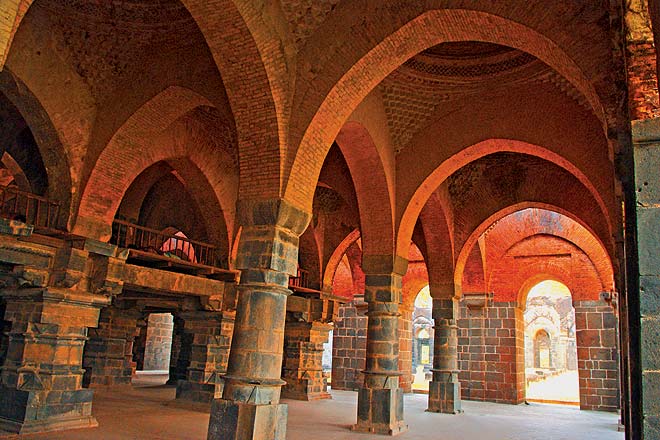

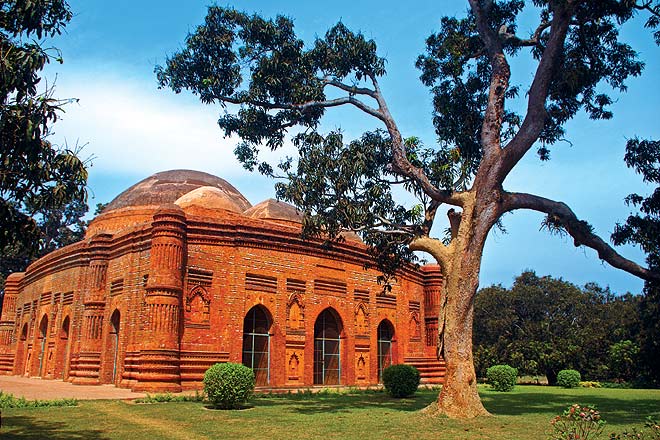

With the Muslim rulers coming to power, this equation changed radically. The new patrons didn’t require exquisite stone idols. Instead, they asked local artisans to use their terracotta art to create geometric and vegetal designs on the walls of Islamic structures. The stone for the mosques was obtained from disassembled non-Islamic structures and combined with brick components. It was only in the later periods that entire mosques were constructed from components designed exclusively for them. Regarding the ornamentation of such mosques, Nihar Ghosh in Islamic Art of Mediaeval Bengal Architectural Embellishments mentions that the ‘panels on the walls, doorways and spandrels including niches are sometimes profusely ornamented by terracotta panels and curved brickworks’.

With the building of several such mosques between 1350 and 1550, the art of terracotta decoration evolved and acquired a position of privilege it hadn’t enjoyed before. Special emphasis was placed on the decoration of the mihrab (prayer niche) and the quiba (western wall).

The Islamic influence, of course, resulted in the absence of representation of human beings and animals in the terracotta panels. Architectural inspiration from Central Asia and the Delhi Sultanate was also evident—for instance, glazed terracotta and the decorative technique of pierced mosaic were imported and introduced. At the same time, Bengali artisans added ornamental designs and compositions derived from folk art, creating a style all their own.

To see some of these existing mosques—and other Islamic structures, such as gates and towers, with similar terracotta work—is to walk through centuries past, the terracotta panels still reverberating with the imagined calls to prayer.

architecture

heritage

Islamic architecture