“Why have we stopped?” I asked Bernard, our boatman. He pointed to the jetty, people were getting

I don’t know what the trader John H. Aspinwall might have thought about the Biennale, but it certainly had all of Kochi enthused. Komu was in a rush, in and out of meetings, as was the curator of this year’s edition, Sudarshan Shetty, but managed to squeeze in a few minutes to chat. “The inspiration of this edition’s theme, Forming in the pupil of an eye, comes from the Vedas,” says Shetty. Known for his sculptural installations, this is Shetty’s first curatorial effort. “It’s akin to a sage opening his eyes after meditation and assimilating the world in that first look, both internally and externally. It’s taken a year and a half to bring this together. The beauty will be in the conversations that the artists from different parts of the world will hold through their artworks.”

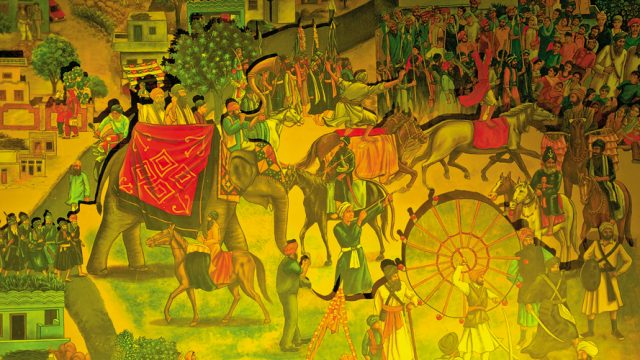

For long, Kochi and Muziris have been home to many communities and become an amalgam of multiple influences.And art being an expression of multiple influences, these seemed to be a natural choice for this multi-cultural event.

Yes, the Biennale isn’t just about one form of art, but the entire creative bouquet. Selva, my photographer, who had been lucky enough to attend the last edition of the Biennale, told me that the area would be abuzz with music and dance performances, art talks, discussions, exhibitions, film screenings and artists and visitors coming from all over the world. And it sounded like a dream for creative ones.

Meanwhile, the old and the new shone in different parts, some walls still needing a fresh coat of paint. A dilapidated wooden boat lay in one corner, probably waiting to be employed as props for an artist. Wooden pillars were strewn on the ground and cement scattered in different corners, but we wanted to meet the artists who were going to bring this place to life for 108 days, from December 12, 2016 to March 29, 2017.

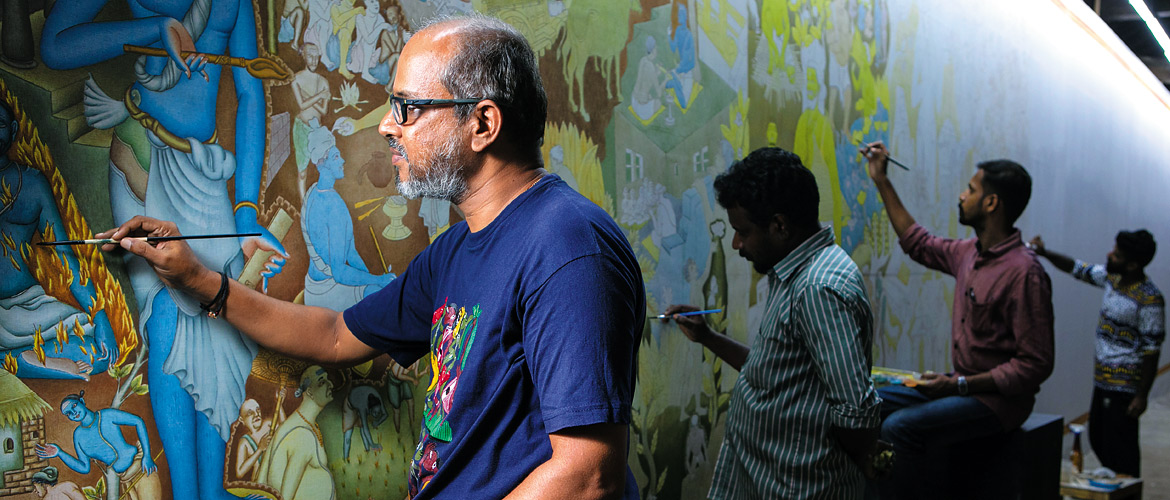

We got lucky. After wandering through some empty rooms, we met P.K. Sadanandan, the Kerala-based artist who was busy with his wall mural that will tell 12 stories. The mythological tales connected to Brahmins and Dalits were being delicately painted with natural stone colours by him and the people he had trained. I didn’t see much of the famous red of the Kerala mural but shades of blues and greens were coming out in the story.

Climbing up to another huge room, labelled ‘Remen Chopra’, we found waves being sculpted on to a red fibre board. The Mumbai-based artist was carving out the pattern of a Persian heirloom carpet which had been passed from mother to daughter over four generations. “I am tracing the landscape from Lahore to Shimla from my grandmother Swaran’s time,” says Chopra. “The red of the board brings out the earthy and feminine aspects.”

More walking and we discovered a room busy and noisy with activity. Delhi-based theatre director Zuleikha Chaudhari was busy putting together a court room. “There is going be a live performance with installations. This court case took place between 1930 and 1946 and moves around proof of identity, an apparent impostor and the inheritance of a large estate,” she explains ardently.

We then walked to the nearby Pepper House, where more art would be experienced. Sculptures enhanced a green courtyard, and the sea at the back is a reminder of the constant flow of time, not stopping for anyone. Once used for storing goods, Pepper House now has a café (which was under renovation), visual arts library, gallery, studios for artist residencies and event spaces. Another storehouse—and Biennale venue—is the Dutch Warehouse, alongside Bazar Road which leads to Mattancherry, which dates to the time when the spice trade was at its peak.

Another popular Fort Kochi hangout space, the Kashi Art Café, will also be brimming with artworks. This erstwhile Dutch property is known for its contemporary art (and excellent coffee and cakes) and houses a permanent collection of artworks that include those of K.S. Radhakrishnan, Pradeep Naik and Riyas Komu. Another Biennale venue is Cabral Yard, where Aspinwall & Co constructed a hydraulic press for coir yarn in 1904. It is named after the Portuguese navigator Cabral, who made the first shipment of merchandise from Cochin in 1500 AD.

Two more venues which I would have liked to visit were David Hall and Durbar Hall. The former is now a café-cum-art gallery run by Kochi elder statesmen, so to speak, the CGH Earth hotel group. The handsome bungalow belonged to David Koder, a Jewish businessman. Built around 1695 by the Dutch East India Company, it is said to have been used to accommodate military personnel during the Dutch occupation. Durbar Hall is close to Kochi’s main railway station. This was built by the Maharaja of Cochin in the 1850s as his royal court.

Multiple beautiful venues, art for free, performances to savour—the Kochi Muziris Biennale 2016 promises to have something for everyone.

While the construction and installations in Fort Kochi were in full swing for the Biennale, we were keen to know what Muziris, the ancient sea port, had to offer.

“Now there is only one Jew family with four people, Namiah, residing in Muziris. Once it was home to almost 3,000 Jews,” Dr Midhun C. Sekhar, museum manager for the Muziris Heritage Project, tells me as we step inside the Paravur Synagogue. Built in 1615, the synagogue is a reminder of the town’s confluence of cultures that thrived here. “Trade was with almost 33 countries,” he adds. Historians have traced the trading roots back to 3,000 BC and the town finds mention in bardic Sangam literature, and in the Greek travelogue Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. Pliny the Elder (1st century AD) has also referred to this ancient port in his Naturalis Historia.

Phoenicians, Persians, Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs and Chinese came here. But the devastating floods of the 14th century wiped Muziris off the world trading map. “Spices, gemstones, clothing and more were exported and imported. Now our attempt is to involve the local people in this green heritage project, giving a thrust to the local economy. There has been a boost to homestays too,” says Dr Midhun. For the Biennale, there is expected to be an installation—no details were forthcoming at the time but surely a treat awaiting those fortunate enough to visit.

There are many museums and sites, but we went to the one at Pattanam where Roman coins were discovered in 1983. From 2007, thanks to the beads discovered by some children in the area, the Kerala Council for Historical Research (KCHR, an autonomous institution) conducted a series of excavations here and unearthed a treasure. Housing evidences of habitation from the Iron Age to Modern period, it is better known as the children’s museum as young ones come here on educational trips. There are semi-precious stones and beads, shards of amphora, Chera-era copper alloy and lead coins, fragments of glass pillar bowls and a children’s corner to play with the shards. There is also a puzzle named tubular jar whose purpose has not been deciphered by experts, as these are open from both ends. This museum also houses an artwork by Riyaz Komu and Vivan Sundaram, titled Black Gold, from the previous edition of the Biennale.

We then headed for prayers at India’s oldest mosque, the Cheraman Juma Masjid, built in the seventh century. According to legend, the last Hindu Chera ruler of that region, Cheraman Perumal had a dream of a half moon and stars and embraced Islam.

A quick snack of yummiest jaggery-filled ada and masala tea at Hotel Kailasam, and we went barefoot to meet the deity of the royal family of Cochin at the Shiva temple in Thiruvanchikulam. At one of the oldest (reportedly 2,000 years old) Shiva temples in South India, watch your step though—sculpted onthe entrance floor are figures of genuflecting women!

With water channels connecting each monument, visitors have a choice of exploring it on Hop-On Hop-Off boats. Because we had only three hours before the museums closed, we were in a hurry. In between we managed a short speed boat ride which is rented out for private tours. Whirring through the rippling waters, we could have been in Venice, the green palm trees hanging low over the water, the branches giving us that ‘visit us again’ wave.

And then another short boat ride to Paliam Kovilakom, a palace presented by the Dutch to the then Prime Minister of Cochin. The Prime Minister’s wooden bed, coated with many medicinal herbs, is a fascinating sight. And off to Paliam Nallukettu—a traditional Kerala home for affluent families. Built in 1786, it adheres to the principles of vastu, like other such structures. Nair society being matrilineal, ‘her’ rules applied. We also met the present matriarch, who graciously let us say our thanks to the family deity in the private temple.

But how could I leave Kerala without a sip of the famous Kerala toddy? A 30-minute search brought us in front of a shack. With seven scandalised men eyeing me, I downed a glass in seconds with a plateful of spicy fish. And then crashed out at the Cherai Beach resort, for just a few hours later I was to return to concrete reality from these dreamy, emerald shores.

The information

Getting There

The airport at Nedumbassery is an hour’s drive from Kochi. Air India, Jet Airways, IndiGo, Spice Jet, have regular flights from major cities. From Delhi, approx fare is ₹8,000.

Where to stay

>Bolgatty Palace & Island Resort (KTDC) (+91-484 2750 500/600; [email protected]; ktdc.com; from ₹5,000)

>Cherai Beach Resorts, (+91-9847231400; +91-484 2481818, 2416949, 6503150; [email protected]; cheraibeachresorts.com; from ₹5,653)

For those who want to be in the thick of things, Fort Kochi has many heritage hotels and

homestays and hopefully you will find a room there near the venues if you are among the early birds.

What to see and do

For what you want to see at the Biennale, visitkochimuzirisbiennale.org.

To know all about the Muziris Heritage Project and what you can explore, seemuzirisheritage.org.

In the old Jew Town post office, get a cancellation of the Magen David for ₹5; see the International Tourism Police Museum; Suresh of Sree Ganesh restaurant, near the Paradesi Synagogue, Jew Town, cooks a yum dosa.

art

Bolgatty Palace and Island Resort

culture